Exploring climate tech: How CO2 removal's scale problem is being solved

I'm pivoting to climate! This is a small window into my past couple of months learning about the challenges (and solutions) of getting to net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

When I was five years old, my parents enrolled me in a small K-8 environmental charter school located in northern Illinois aptly named Prairie Crossing. There, I received a wonderful education comprised of trips to the local farm and greenhouse, readings of Aldo Leopold’s The Land Ethic, and blissful annual camping trips across the Midwest’s most magical national parks.

Instilled in us was a profound respect and love for the natural world which inspired my first climate project in 7th grade — the installation of a bioswale to restore wetland habitats and fix the ongoing erosion problem on my school’s campus. The two-year project was a formative experience and gave me a surprisingly helpful, though obviously very simplified, picture of the challenges of building in climate.

The research and science were foundational. Our proposal took a few months alone, requiring us to become deeply acquainted with the problem of erosion and evaluate all the possible negative externalities of potential solutions. Funding was one of our largest hurdles: my partner and I won a grant and crowdfunded over $1K just to acquire the necessary materials. Policy was another. Before we could start leveling the land, we had to work with a government association to ensure we complied with all the necessary regulations. Measuring impact was hard — our advisor warned us that the positive effects of our work might not materialize for at least a year and even then, it would be hard to quantify how much we really helped.

When I made the decision to pivot my career to climate tech, I found myself thinking about this middle school project. The analogy is admittedly a bit silly but I realized that historically (non-software) early-stage climate tech startups take a long time to commercialize because they also require a substantial amount of initial funding, govt. support and regulatory expertise, robust supporting research/data (longer product development), and reliable ways to measure impact (hard to do in cases where there are no widely agreed upon standards), with the added necessities of “proof of scale” and enough initial customers.

Until now, the challenge of commercialization and deployment was especially difficult for climate startups working on removing CO2 emissions from the atmosphere. But before we delve deeper into why and what’s changed, let’s zoom out to understand how the CO2 removal industry came to be.

The current state of CO2 emissions

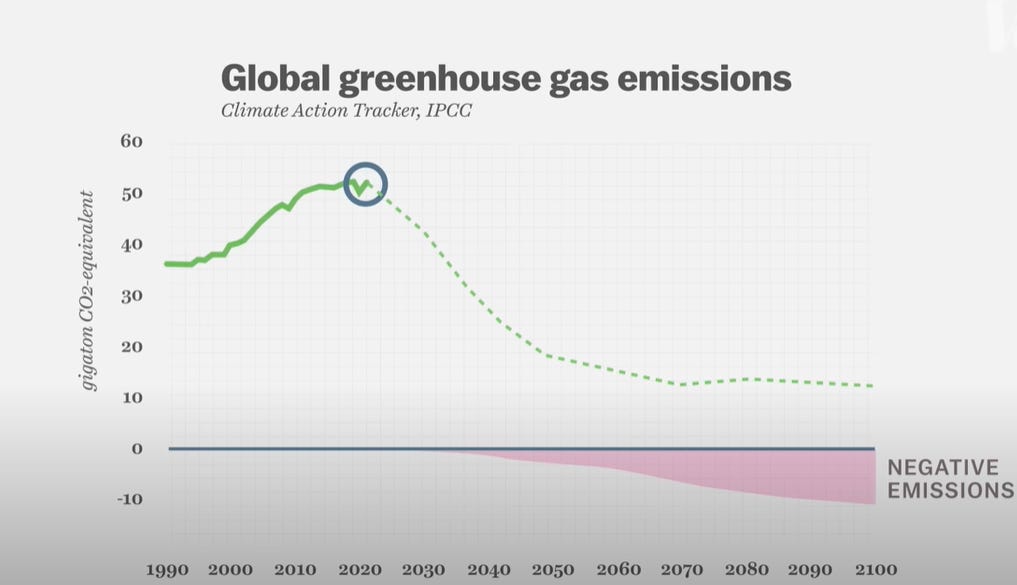

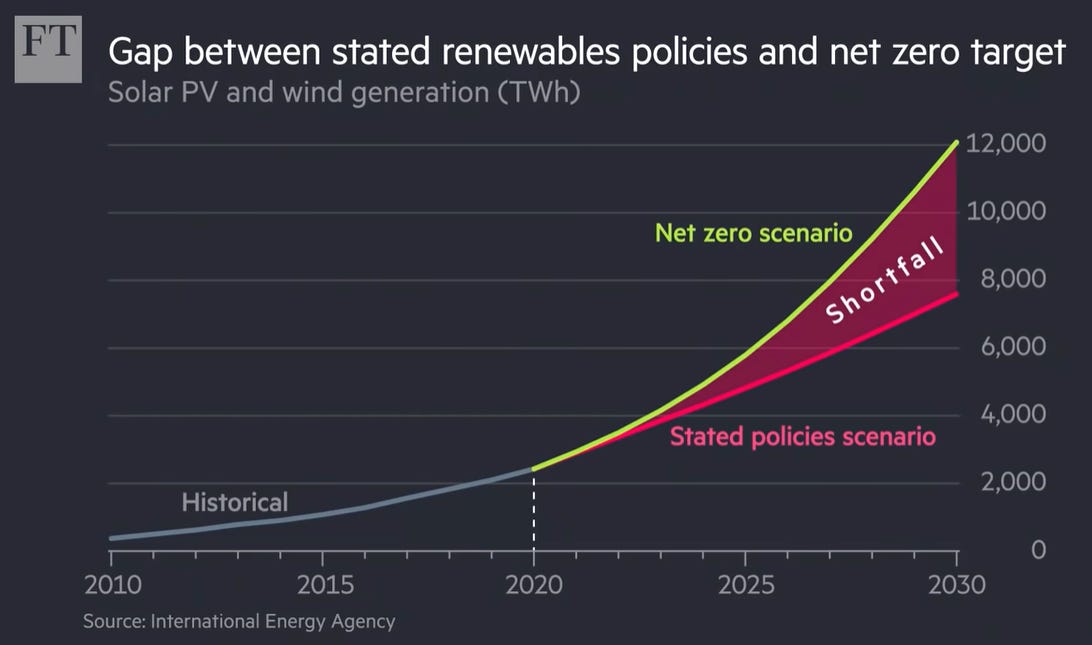

In order to prevent the irreversible and disastrous consequences of climate change, the Paris Agreement says we need to limit global warming to well below 2°C and pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5°C. This requires slashing emissions by 45% by 2030 and reaching net zero emissions by 2050.

Unfortunately, we’ve made very little meaningful collective progress since the agreement’s inception and are now at a critical stage where even if we reduced emissions to zero today, there would still be too much carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. (CO2 in the atmosphere is 420 parts per million today — a 50% increase from pre-industrial levels). This means our only fighting chance at reaching the 2050 target and reducing global warming is to take carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

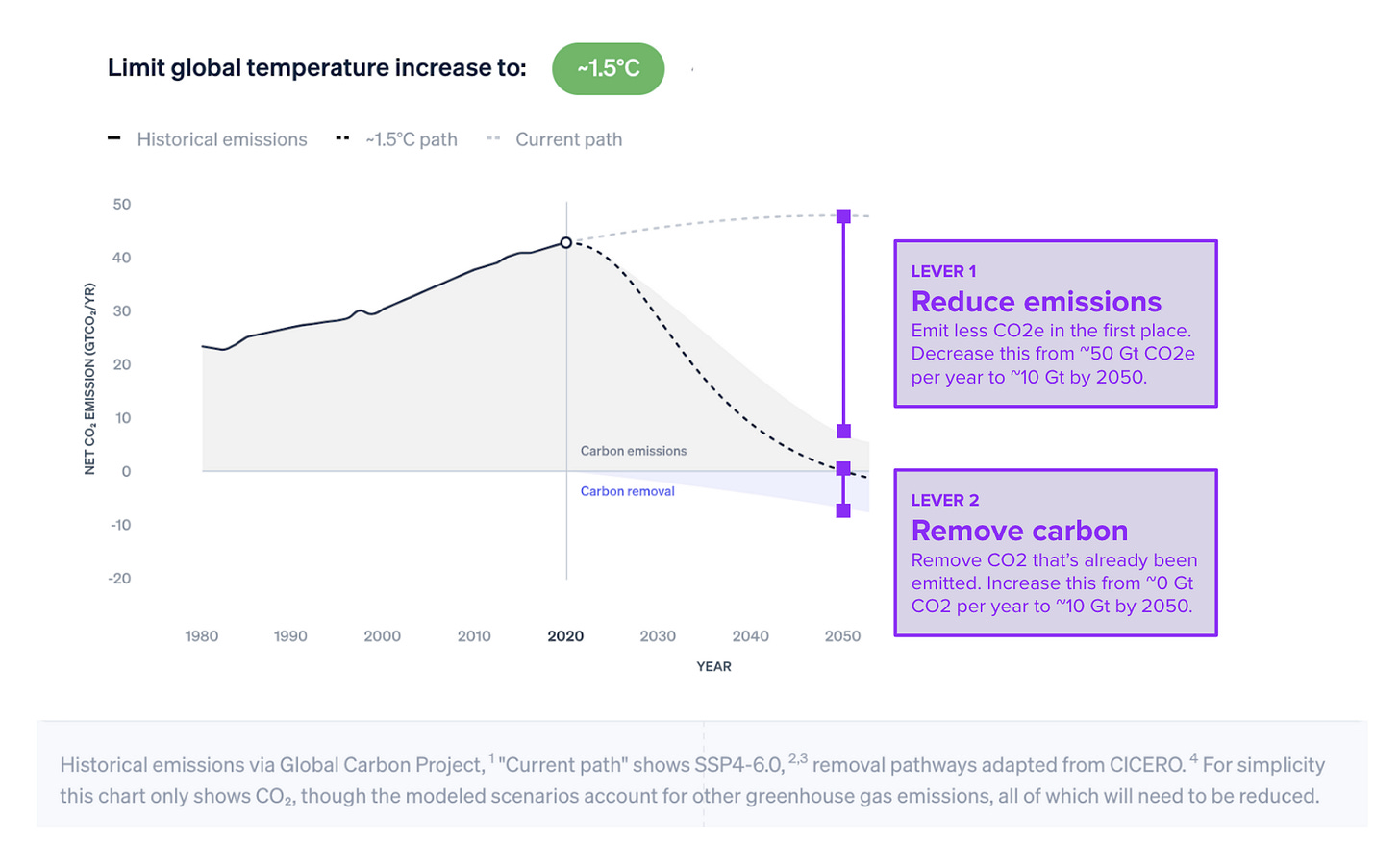

While experts agree that a vast majority (90%+) of efforts should be focused on reducing emissions and the adoption of clean energy at scale, many also agree that carbon dioxide removal (CDR) must now be a part of the solution, too.

Note: Nan Ransohoff, Head of Climate at Stripe, has an extraordinarily helpful article titled A mental model for modeling climate change that broadly outlines six ways to reduce emissions <10 Gt per year. This includes electrifying devices that consume energy, powering devices with clean energy, updating the electric grid, decreasing land use (while increasing efficiency), and decarbonizing agriculture (food-growing) and heavy industry facilities as fast as possible.

The article also includes an introduction to the carbon removal market which I’ll explore in more detail below.

Carbon removal: The scale problem

To understand the science behind carbon removal, I recently completed a course on CCS: Carbon Capture and Storage by The University of Edinburgh via edX that I highly recommend. I also found this 20-min video by The Financial Times to be an informative entry point for understanding the current stage of the technologies and various sentiments in adopting it as a solution. I reference it heavily below.

The (very simplified) TL;DR is that the technology is mostly there, but the scale isn’t.

From my understanding, carbon removal technologies are fairly straightforward. It’s now less of a question of how to remove carbon (there are many proven methods), but rather how to do it quickly, affordably, and at scale.

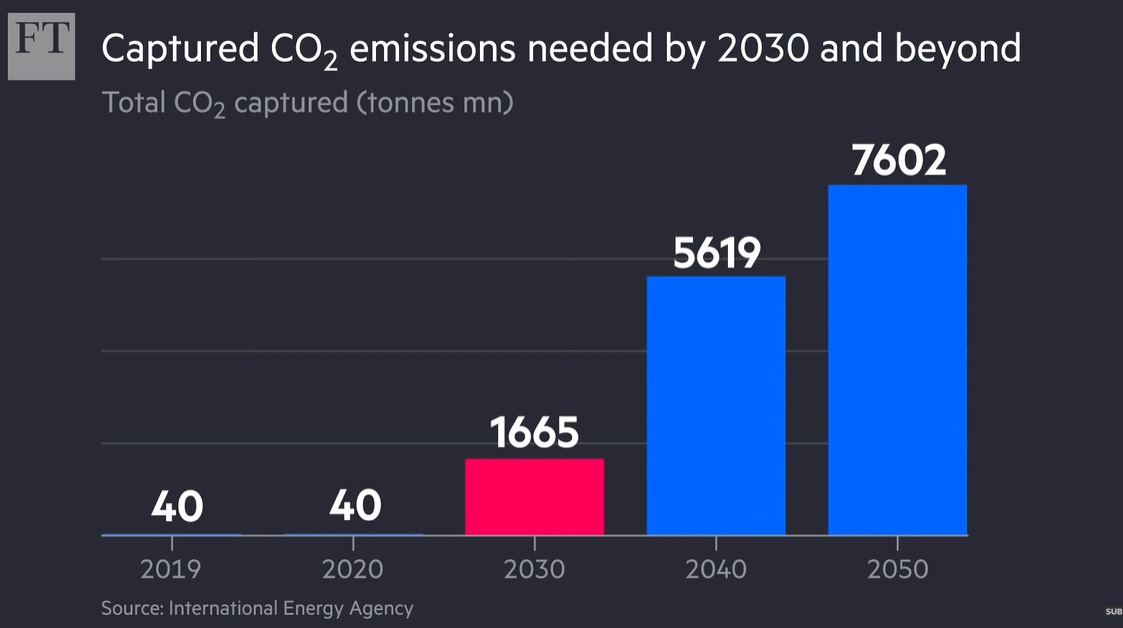

In the Financial Times video, clean energy correspondent Leslie Hook explains that in 2021, there were about 40 million tons of CO2 captured by existing carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies. “But that number would need to rise to around 1.7bn tons of CO2 by around 2030. That’s a 40x increase in just the next eight [now seven] years.”

Estimations for how much carbon removal is needed can differ based on the various predictions of our ability to reduce emissions globally. Below is a graph from Nan’s mental model article. She writes, “Roughly, we need to decrease emissions from 50 Gt per year to 10 Gt per year by 2050. We need to increase carbon removal from ~0 Gt to ~10 Gt per year.”

The bottom line is these negative emissions technologies need to scale drastically. Bob Maughon, Chief Technology and Sustainability Officer at chemical manufacturing company Sabic, explains “Whether it’s the carbon capture scale or it’s the transport and storage scale, all of those are driven to lower economic costs by increasing the size.”

A central issue preventing achieving the desired scale is that CCS and other negative emissions technologies don’t have many customers because carbon removal and storage are not practically useful to most companies. Because carbon removal isn’t a revenue source, companies lack an economic incentive to invest in it.

Another effect of the lack of a natural market for carbon removal is that it drives away entrepreneurs, decreasing innovation and competition in the space. And venture capitalists have no incentive to back startups focused on carbon removal either.

How we’re currently tackling the scale/demand problem

Voluntary markets — Stripe Frontier is an advance market commitment (AMC) to buy $1B+ of permanent carbon removal between 2022-2023). It’s one of the coolest solutions and I explore it more below.

Venture Capital funding — Lowercarbon Capital is a huge player here. Voluntary markets give VC funds like LC an incentive to fund CDR startups. More on that below, too.

Government funding — Ex. the U.S. Energy Department pledged to invest $3.7B in carbon removal last year. Governments are important early customers. (Also see the Inflation Reduction Act’s impact on decarbonization).

CCUS — Carbon capture usage and storage. This is where come of the captured CO2 is reused in industries where CO2 is “absolutely crucial and there isn’t currently an answer for replacing its usage.” Plastics and fertilizer industries are two potential customers of this.

Stripe Frontier: The AMC Model

Stripe Frontier was founded by numerous companies including Stripe, Alphabet, Meta, McKinsey, and Shopify. On The a16z Podcast, Steph Smith talks to Nan Ransohoff — Head of Climate at Stripe — about The Economics of Carbon Removal.

To tackle the lack of a natural market for CDR, Frontier became the first big “customer” for carbon removal startups taking inspiration from the first-ever AMC. Nan explains what an AMC is in this interview with Packy McCormick for Not Boring:

AMCs are a concept we borrowed from vaccine development. In the early 2000s, low-income countries lacked access to the pneumococcal vaccine. Pharma companies weren’t motivated to spend resources developing a low-cost vaccine because they were unsure there’d be enough demand to recoup their costs. So governments and philanthropists came together and pooled $1.5bn in subsidies. Their promise was: if the pharmaceutical companies could produce the vaccine at low cost, they’d have customers to pay for them. The program delivered hundreds of millions of doses, and by some estimates saved almost a million lives.

Frontier is conceptually similar. Stripe, Alphabet, Shopify, Meta and McKinsey have pooled an initial $925M of demand to buy permanent carbon removal over the next eight years. Frontier’s team of technical and commercial experts vet suppliers to identify the most promising technologies, and then facilitate purchases between buyers and suppliers. Frontier offers pre-purchase agreements to early stage companies and offtake agreements to larger, more mature companies looking to scale. With guaranteed customers, suppliers can secure the financing needed to build their next plant, and more generally, to scale up.

Basically, Frontier is willing to overpay early-stage CDR startups right now to help stimulate the market and move the cost curve of CDR technologies down so it’s cheaper for customers later.

Nan explains that the first step in creating a market for CDR requires voluntary markets (where players are primarily motivated by philanthropic reasons). After that, the market’s sustainability will likely require policy to continue stimulating it and ensuring there are other corporate customers. “That could be in the form of direct government procurement… [or] the government creating a compliance market effectively by pricing the negative externality of a ton of CO2 and pushing that on to private companies and emitters.”

Lowercarbon Capital

Chris and Crystal Sacca’s fund Lowercarbon Capital splits investments into three buckets:

For this article, I’m mostly interested in the second: Sucking up carbon. In this article, Chris explains, “When it comes to demand for carbon removal, consider that two years ago, the amount of money trying to buy it rounded down to $0. The few companies attempting removal were basically small demonstrations with no clear path to scaled commercialization…For years, without customers willing to pay up, investors weren’t backing novel solutions.”

But thanks to Stripe as well as commits from Microsoft and Airbus, that number is over $1B and likely going to grow with more voluntary markets. Chris explains that this, coupled with the amount of innovation now happening in CDR, makes carbon removal an attractive space to invest in. I think it’s pretty neat that Frontier launched last year in April 2022 and within a couple weeks, venture firms like Lowercarbon were ready to start writing checks.

Brief tangent on the state of climate tech

Chris talks to Stanford adjunct lecturer Ravi Belani about “why he thinks we’re entering a golden age of tech-driven climate solutions” on this podcast. Chris explains that he’s sensed a shift in the market where for the first time, we’re seeing major players in carbon-intensive industries such as agriculture and aerospace investing in clean tech because of their greed (“digging up fossil fuels is expensive” and clean tech offers the more cost-effective solution.)

This observation reminded me of independent researcher Nadia Asparouhova’s article Mapping out the tribes of climate in which she identified seven primary camps of beliefs regarding the “right approach” to tackling climate. She explains that folks in climate tech have an abundance mindset. Here’s a snippet from Nadia’s article that helped me understand what that means in the context of climate:

Lyn Stoler and Sonam Velani [who are in the climate urbanist group] recently introduced the term “climate industrialism”, which they describe as an “optimistic, action-oriented response.” Like energy maximalists, they believe climate solutions are directly correlated with economic growth and “[reject] the idea that climate solutions have to be rooted in scarcity and sacrifice. Instead, it’s a bet that climate solutions rooted in abundance and progress can and will create value for people in their daily lives, homes, communities, and cities.”

Lots of interesting stuff in Nadia’s article but Substack’s giving me an article limit warning so back to carbon removal!

The moral hazard problem

As promising as CDR and CCS sound, they’re not without controversy either.

Direct air capture (CCS) was actually originally used for enhanced oil recovery (EOR), a process where oil companies extract more fossil fuels by injecting “pressurized CO2 into old oil wells to increase the pressure inside the reserves, and therefore dislodge the remaining hydrocarbon.” Myles McCormick, US Energy Correspondent at The Financial Times, touches on the irony of this: “A technology that is used at the moment to try to limit the worst effects of global warming was developed in the first place to produce more fossil fuels.”

This relates to the moral hazard problem: Does CCS (and CDR) give oil and gas companies — and other industries in general — an excuse to continue “business as usual” without reducing their emissions?

The short answer: Potentially, but we still need CDR.

(A possible solution here is to use policy to create different mandates for emissions reductions and carbon removal instead of lumping both of them together in a singular “net zero” target. This would prevent companies from procrastinating their commitments and over-relying on CDR).

Carbon removal isn’t a silver bullet. But this is why it’s necessary.

Grete Tveit, Senior VP at Low Carbon Solutions Equinor, explains in the Financial Times video that “Renewable is developed today at scale, and we really believe in wind, but we need much larger scale of renewable. And until we have that scale of renewable, we would need CSS to bridge that.”

Zeke Hausfather, the climate research lead at Stripe Climate and a contributing author to the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, and Jane Flegal, the market development and policy lead at Stripe Climate explain the real risks of the moral hazard problem but explain why it’s still going to have to be part of the solution.

There is…a real risk that stigmatizing carbon removal over moral hazard concerns creates an even greater danger: deferring much-needed investment and imperiling our ability to reach future climate goals. Unfortunately, after decades of delay, there are now simply few paths to meeting our climate goals that don’t require both slashing emissions today and building the capacity to suck up vast amounts of carbon dioxide in decades to come.

—

I’m unfortunately at the article limit but hope you found this brief snippet of my notes from learning about climate tech and the CO2 removal space interesting! I plan to continue documenting my learnings and dive further into the above sections in future posts.

Reach out to me at ashritha.karuturi@gmail.com if you’re interested in connecting!

Love how well you break this down, best of luck for your next steps!